First let’s congratulate the following new contributors, who made their first commit to the project during the past months:

For a long time, this project only disassembled the source code for a single version of the game: the US v1.0 release.

A few months ago, Marijn van der Werf started to add support for the German version of the game.

Not an easy task. Not only the dialogs differ from the US version, of course – but there are quite some more differences: a few tilemaps (like the translated Game Over screen), some tiles (e.g. extra alphabet letters), a handful of regional differences…

But in the end, after carefully finding all the differences in the game resources and code, and storing the differences with the baseline English version into German-specific files, Marijn managed to add German support to the disassembly.

The File Selection menu in all its German glory.

But Marijn didn’t stop there.

While he was at it, he casually added support for every version of the game ever released.

In all languages.

Japanese v1.0? Got it. French v1.2? Here you go. English v1.1? There it is.

It is now easy to study the Japanese or French games: they will be compiled along the other versions.

These versions all have many small differences between them. Some places were improved, some bugs were patched. Supporting all these versions meant identifying each of those small changes.

Some changes are obvious, like the Title screen between languages.

But other patches are much more subtle.

Moreover, the version are not linear: some patches applied to the Japanese 1.1 and 1.2 versions are not present in other languages’ 1.1 and 1.2 releases.

Fortunately, Xkeeper took some time to research and document these patches: when they were written, what they do. The resulting matrix accurately the complexity of the actual revisions:

| - | JP 1.0 | JP 1.1 | JP 1.2 | US 1.0 | US 1.1 | US 1.2 | FR 1.0 | FR 1.1 | DE 1.0 | DE 1.1 |

|:-------------:|:------:|:------:|:------:|:------:|:------:|:------:|:------:|:------:|:------:|:------:|

| `__PATCH_0__` | | Yes | Yes | | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| `__PATCH_1__` | | | | | | | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| `__PATCH_2__` | | Yes | Yes | | | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| `__PATCH_3__` | | Yes | Yes | | Yes | Yes | | | | |

| `__PATCH_4__` | | | Yes | | | Yes | | Yes | | Yes |

| `__PATCH_5__` | | | | | | | | | Yes | Yes |

| `__PATCH_6__` | Yes | Yes | Yes | | | | | | | |

| `__PATCH_7__` | | | | | | | Yes | Yes | | |

| `__PATCH_8__` | | Yes | Yes | | | | | | | |

| `__PATCH_9__` | Yes | Yes | Yes | | | | | | Yes | Yes |

| `__PATCH_A__` | 1 | 1 | 1 | | | | | | 2 | 2 |

| `__PATCH_B__` | 1 | 1 | 1 | | | | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| `__PATCH_C__` | | | | Yes | Yes | Yes | | | | |

Read the full patches notes to get a idea of what each patch does.

Also, people at The Cutting Room Floor have been documenting the version differences for many years now. So now it’s all a matter of matching the differences in the code to the observable behavior changes.

With this massive work, the ZLADX disassembly can now build ten different revisions of the game, with exact byte-for-byte compatibility.

Sprites modding has been a feature of the ZLADX modding community for a long time. Popular randomizers like Z4R or LADXR allow you to customize the characters visuals by replacing the spritesheets.

However, until now, the spritesheets in the disassembly were not easy to edit. Actually, they were in a sorry state.

Well, that’s not all bad: spritesheets were stored as PNG files, which makes them easy to view, and automatically converted to the Game Boy 2bpp format at compile-time. But many things were confusing in those PNG files. Here’s for instance how the first Link’s sprites appeared in the disassembly:

This raw dump of the sprites to a PNG file is not very clear.

It hard to see anything. That’s because this is a raw conversion of the in-ROM 2bpp tiles format to a PNG file. No other conversion is made, which causes the picture to be hard to read.

There are two things missing here.

First, the colors are wrong. Or, more precisely, the grayscale is wrong. When running on a Game Boy Color, the colors are applied at runtime, by matching each tile with a separately-defined color palette. So even on the Game Boy Color, graphics remain stored as grayscale, with 4 possible gray values.

But on the picture above, what should be rendered as the blackest gray value is instead rendered as white. And other grays are wrong to.

Contributor @AriaHiro64 found a fix for this: by tweaking the PNG file to reorder the indexed colors table, they were able to fix the grayscale values – while still retaining compatibility with the tool that transform these PNG files into 2bpp files at compile-time.

Proper color indexation already makes it more legible.

Still looks like a puzzle though.

Now it’s easier to see the other missing element: the tiles are not ordered in the most natural way.

This is because on the Game Boy, sprites can be either a single tile (8×8 px) or two tiles (8×16 px). And on Link’s Awakening, most characters made of sprites are at least 16×16 px – that is, each character is composed of two 8×16 sprites stitched together vertically.

So tiles for sprites often differ from tiles used to store background maps. Tiles for background maps are usually stored horizontally, from left to right, as:

1️⃣2️⃣

3️⃣4️⃣

So the conversion of background map tiles from 2bpp tilesheets to PNG is straightforward.

But tiles for sprites are usually stored vertically, from top to bottom, as:

1️⃣3️⃣

2️⃣4️⃣

So naïvely converting a spritesheet to a PNG file yields tiles ordered as 1️⃣ 3️⃣ 2️⃣ 4️⃣, which will look wrong, exactly like on the picture above.

To solve this, we have to go through a process named interleaving: when extracting the original tiles to a PNG file, we fix the tiles ordering by de-interleaving them. The resulting PNG file then has the tiles in the proper order.

And at compile-time, when transforming the PNG files to to the native 2bpp format, the same Python script interleaves the tiles, back to the original representation.

When properly de-interleaved, Link’s sprites appear in their full glory.

To make this process easier to automate, a simple Make rule specifies that all PNG files prefixed with oam_ are automatically inverted and interleaved at compile-time.

So thanks to these conversion steps, now all spritesheets of the game can be easily browsed and edited. Have a look!

A few months ago, in the disassembly source code, background tilemaps were all stored sequentially in a single ASM file.

This was suboptimal for many reasons:

But since June, the situation greatly improved. First, Daid wrote a tool to parse the data format used by the tilemaps, and decode the data as readable instructions.

Then another PR identified and named the tilemaps. And last, all tilemaps are now exported them as individual binary files. So you can simply browse the tilemaps, and peach.tilemap.encoded will contain the data you expect.

Having separate files also makes easier to compare the differences between the successive revisions of the game. Before, all tilemaps were stored for each revision. But now only the tilemaps that actually differ from revision to revision are stored (usually mostly the file menus, because they include text that had to be localized).

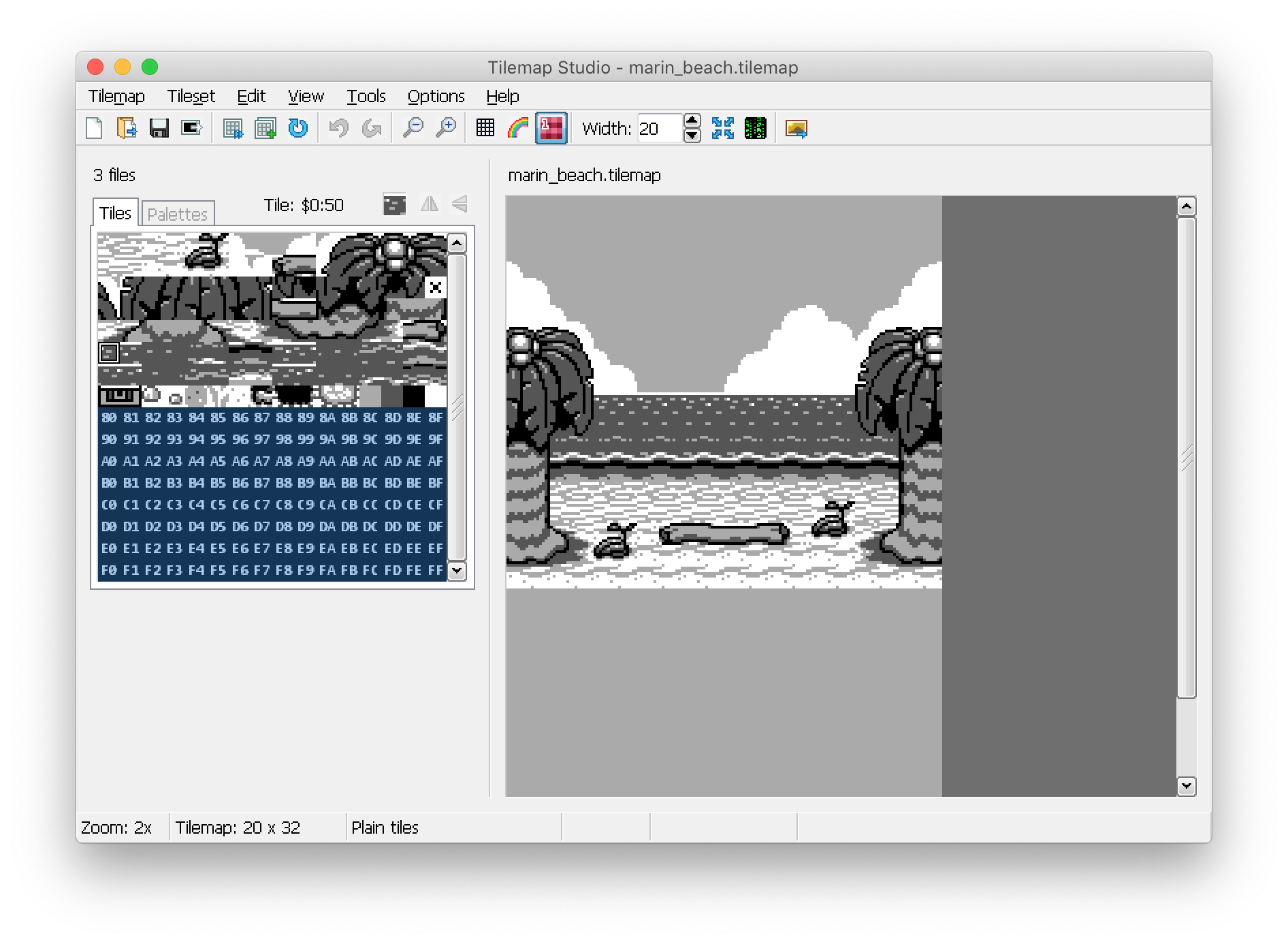

Tilemaps can now be edited graphically using standard tools, like Tilemap Studio.

Ideally, the tilemaps would be stored in a decoded, easily manipulable format (that is, as a raw sequence of tile identifiers). And at compile-time, they would be re-encoded into the format expected by the game engine.

But unfortunately, when developing the original game, the encoded tilemaps were not machine-generated from decoded files. Instead they were hand-written by the original developers. So if we used an automated tool to encode the tilemaps, we wouldn’t get exactly the same result than the hand-written encoding: it would be functionally similar, and produce the same tilemaps, but the exact bytes wouldn’t be the same. Which means we would no longer have a byte-for-byte identical ROM.

Instead, the files are stored in the original encoded format. And to made them easier to edit, the disassembly now includes a command-line tool to decode the tilemaps to the raw binary format suitable for import into tilemap editors.

On a smaller note, Daid documented the initialization values used by the fishing minigame.

Did you ever want to build a custom version of the game with only the bigger fishes? Now is your chance!

Wow, fishes in this pond sure must be well-fed…

Of course many more improvements were done in the past months, much more than what is presented there.

And as for next steps, although the tilemap values are now decoded, the tilemap attributes are not. As the attributes associate a tile to a color palette, that means editing the tilemap colors is still harder than it should be. Fortunately, the tilemap attributes are stored in the same format than the tilemap values, so writing a tool to decode them should be straightforward.

Also the high-level engine documentation is still evolving. It started as an incomplete description of the various systems of Link’s Awakening game engine, but is becoming more and more fleshed out. Many topics are still waiting to be explained though.